![IMG_20150425_153959]()

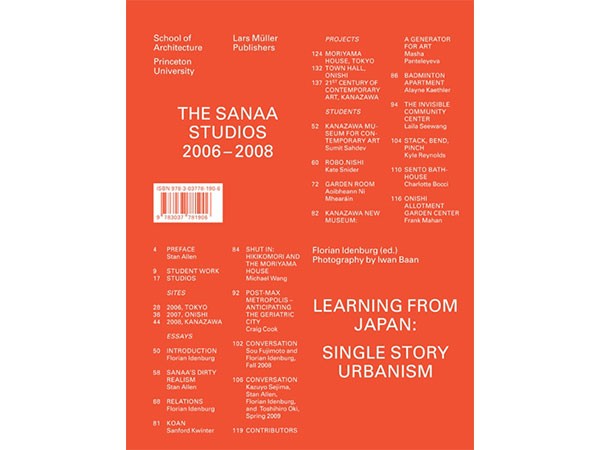

A peculiar day-trip took citizens of Ontario’s capital on an exploration of the history and revitalisation of Southern Ontario’s other major urban centre. It’s Hamiltime and Emily Glazer has filed this report on what they saw. She is a writer, health researcher, and advocate in Toronto and co-hosts Alleycats on the Toronto Radio Project exploring urban tales and trails. She is also a community leader for the Samba Elégua percussion group.

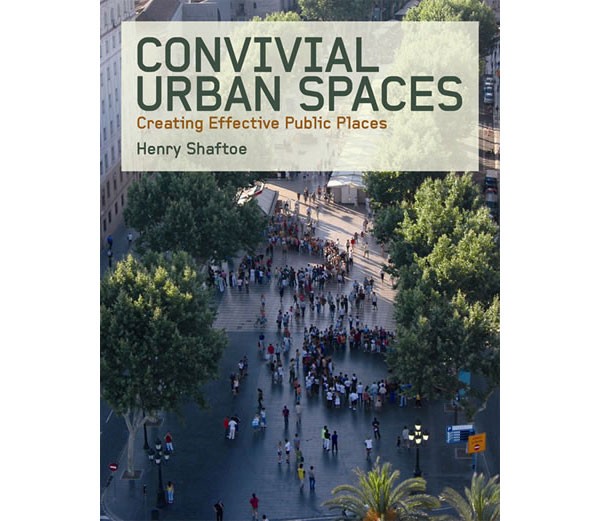

Fifty Torontonians pile onto a schoolbus and head to Hamilton for a daytrip organized by Toronto-based Civic Salon and the Young Urbanists’ League (YUL) on April 25th. The idea was to foster better ties between the two biggest Greater Toronto and Hamilton Area (GTHA) cities. The result was an on-the-ground lesson in urban revitalization thanks to what’s going on in Hamilton, and some instructive clues for strengthening the region’s cohesion.

Sponsored by Evergreen Cityworks, the sold-out tour affectionately called “Hamiltime” bustled between Hamilton’s rich naturescapes and urban clusters like the downtown and sprawling industrial zones. But Civic Salon organizer Jo Flatt was drawn most to the human engine behind Hamilton’s revitalization. “After spending time there I realized that there are a lot of amazing people who are doing great things to transform the city,” reflects Flatt. “I was amazed at the level of community-led initiatives that are making the city better.” Rachel Lissner, founder of the YUL, wanted to Torontonians to expand their horizons. “It is really important to remember that geographically, socially, economically, and politically, we are part of a greater region and we should be aware of what is going on beyond our mostly-porous borders.” Flatt and Lissner linked with local guides Peter Topalovic (Transportation/City of Hamilton), Chelsea Cox (Social Bicycles or SoBi, Hamilton’s bikeshare) and Jay Carter (Evergreen Cityworks).

![IMG_20150425_094154]()

As the day-trippers could attest, more interesting than ideas for integration are the things that have recently kept these municipalities apart. “It is surprising to me how close Toronto is to Hamilton and just how few of my friends and colleagues have ever been there,” muses Flatt. Is it something about Hamilton’s faded rust-belt past, the Torontonian’s penchant for never leaving home, or something more akin to a lack of regional imagination which prevents the Golden Horseshoe from blossoming into an Ontario equivalent of the Bay Area in California? Of late, however, a number of forces have collided to knit the GTHA closer together such as punishing housing costs in Toronto, the scramble for infrastructure to host the Pan Am Games, and a grassroots-led revival of Hamilton.

On the ground, the tour made sure to showcase Hamilton’s proximity to nature, beginning the tour at Webster Falls inside of Spencer Gorge, and later visiting Albion Falls. Head of Watershed Planning and Engineering Scott Peck spoke of Hamilton’s 147 waterfalls, a blessing of the Niagara Escarpment that snakes through the city and creates its famous mountain and plain divide.

![IMG_20150425_100327]()

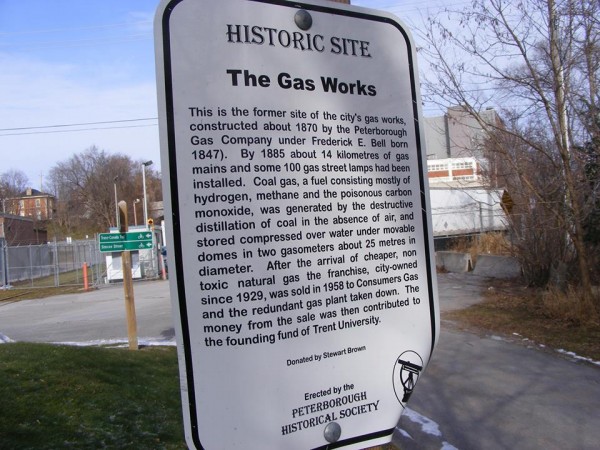

In the East End, Hamiltime ventured past the smokestacks often scorned by inhabitants across Lake Ontario. The cloudy blooms are reminders of the heydey of the “Ambitious City” where Dofasco and Stelco fed the city with steel and prosperity then declined with the surge in trends like outsourcing, globalization and automation.

![IMG_20150425_100827]()

Today the biggest employers are the academic and hospital sectors centred around MacMaster University, explained Jason Thorne, himself a recent returnee to the Hammer. Thorpe is the head of Hamilton’s Department of Planning and Economic Development. He spoke to Hamiltime amid the antique and textile shops on Ottawa Street North in the heart of the east end which used to be a low-density, post-war community of steelworkers. Now it is an increasingly mixed neighbourhood with newcomers to Canada, and is the site of what Thorpe refers to as a “third wave of revitalization.” But in contrast to Locke and then James streets that had previously revitalized, Ottawa is being renewed with existing infrastructure. “It’s revitalization without completely re-doing the streetscape,” says Thorne. The lots are narrow, not conducive to new developments. Vacant storefronts were plentiful, but the vacancy rate went from forty to just two percent within seven years. The areas’ affordable houses are also drawing Torontonians who can no longer pursue a middle-class lifestyle complete with home ownership in Toronto. “A lot of exciting stuff, even though I’m a city bureaucrat, is really not to do with the city,” adds Thorne. “It’s is a very grassroots citizen-led revitalization.”

![IMG_20150425_150229]()

One important component of Hamilton’s resurgence is the updating of its industrial narrative. Environmental stewardship is integral. Linda Lukasik, Executive Director of Environment Hamilton, is a model of citizen change-making. In 2001, Lukasik sued the municipality using the Ontario Environmental Bill of Rights and won. One Environment Hamilton project is Stack Watch, which arms citizens with the knowledge to document problematic emissions and report them to the regulators, holding companies accountable.

![IMG_20150425_143424]()

Another success is the Windemere Basin. “This is an amazing area, I love it,” beams Lukasik, speaking to Hamiltime on the Basin’s created wetlands. “To me this story is all about Hamilton and transformative change, and taking a rust-belt city and doing exciting things.” Formerly a deposit for dredged shipping channel waste, the reclaimed east bay is now a flourishing wetlands supporting native fish, birds and plant growth. And it happened with a mosaic of actors: “People in this community are really engaged. You have a lot of interesting multi-stakeholder collaborations like the remedial action planning process where organizations like mine will sit at the table with industry, the universities and all levels of government, community members, and people all come around the table.”

![IMG_20150425_141530]()

Downtown Hamilton is also being revived with a suite of pedestrianised spaces, preservation of old buildings and small business incentives. Hamiltime strolled down Gore Park – the pedestrianised south side of King Street East – and listened to Glen Norton, Manager of Urban Renewal in Hamilton’s Planning and Economic Development Department. He described the loss of big companies like GE in the 1990s from the downtown. Shops were shuttered and buildings emptied. Even the iconic Royal Connaught Hotel, once inaugurated by a member of the British Royalty, sat idle. Worse, buildings like the old city hall – a French Romanesque jewel in the style of Toronto’s old city hall – had been knocked down earlier for a rendition of urban renewal that erected massive shopping centres across several city blocks. These sprawling and squat chunks of concrete have their backs to the street, like Jackson Square at James Street and King William.

![IMG_20150425_154121]()

Norton lauds the efforts of local developers acquiring idle buildings downtown and creating new condos and restaurants, encouraged to preserve old architecture with a $20k city grant program for facades. The land housing the Tivoli Theatre, once Canada’s oldest-running cabaret, was approved for a 22-story condo on the condition of restoring the theatre. The Listor Bloc, built in 1924, was given a $26 million restoration and contains the city’s arts and culture department.

But the manner of development gives many locals caution, weary of going down the Toronto route of towering glass condos which pierce the skyline and the eye and where keeping a building facade is seen as preservation enough. A Manhattan feel at a Tower of Babylon pace. It seems a low-bar for city-building. Other downtowners, however, are starved for densification after years of hollow living and are thirsty for tall towers.

There is justified anxiety about the Toronto-Hamilton romance in the Hammer, which is an unequal power relationship after all. Some of the tourists noted how it can take an hour to cross Toronto to get to work downtown; when inter-city transit improves, why not be living in a bigger and cheaper space within a smaller, still-urban city? But Hamilton doesn’t want to be a bedroom community for TO. It clearly isn’t any kind of room in another edifice at all, and during Hamiltime its stand-alone muscles were showing.

One of the most popular civic engagement websites in Canada is Raise the Hammer. Founder and editor Ryan McGreal spoke to Hamiltime while overlooking the downtown from another escarpment viewpoint on Mountain Brow Boulevard. He noted another key to Hamilton’s downtown revival: changing the flow of traffic on streets that were flipped into one-way thoroughfares one gloomy night in the fifties. Opening streets to bidirectional flow encourages stops, walking, shopping and perusing, but takes away fast passage through downtown. And thus emerges the urban/suburban divide Torontonians know intimately, although in Hamilton it didn’t produce a Rob Ford.

![IMG_20150425_113951]()

James Street North was the first street to be converted back in the early 2000s, fitted with bump-outs and two-way traffic. From the ’90s until then, city council was tenacious. “The council of 15 years ago was so desperate that they laid the groundwork for prosperity and revitalization”, said McGreal. “When we make bold moves, we can actually make changes pretty fast.” Now the changes are painstakingly slow; council has started to coast, moving away from an activist agenda now that the downtown is doing better. McGreal notes the rust-belt mentality still haunts Hamilton in its attempts to lure external companies to consolidate their operations, rather than laying the groundwork for the next big companies to start from Hamilton seeds. McGreal echoes Thorne’s excitement about reusing existing fabric: “A lot of what energizes me is meeting people who moved here recently, who don’t see the legacy of 20 years of frustration and all the politics; they just see the opportunity … they see this fantastic old building that’s just sitting there waiting for someone to buy it and pour some love into it. This city is filled with that kind of opportunity and we need people with a fresh set of eyes to come and remind us of what we have and how beautiful this place is.”

From one vantage point the downtown renewal is visible. But can urban renewal be confined to new condos, their residents, and new places to eat? Hamiltime proceeded down James Street North, the epicentre of downtown gentrification. Sure, Hamilton’s renewal has been fiercely grassroots-driven: the famous Art Crawl and Supercrawl draw over 150, 000 people (in a city of 550 000) and were conceived and organized by artists. Hamilton boasts one of the greatest volunteer rates in the country. On the other hand, as intrepid community activist Peter Hopperton described to Hamiltime, gentrification often means displacement of local interests in the name of profit. There is a reason old buildings are left to decay by speculators until they’re lucrative, Hopperton noted. And once a cultural milieu is generated by artists drawn by cheap living and derelict buildings, it becomes commodified by developers who use the culture as a brand. Artists become sacrificed on the frontlines of gentrification, eventually priced out. It’s the usual story.

Attendees of Hamiltime were mostly 30-something downtowners of TO who hadn’t ventured to Hamilton before; some were curious about cheaper rents, many were already engaged in social enterprise and city exploration. One had found love in Hamilton and came to learn more about the city. For Elizabeth Littlejohn, a professor of sustainable design and social innovation at Sheridan College, Hamilton represented a viable place for living later in life, and a refuge from some of the poor decisions made in Toronto of late. “Since the reign of the Fords, they did a lot of damage to Transit City. They’ve done a lot of damage that’s long-term to transit infrastructure in Toronto, and a lot of very poor decisions have been made.” She also cites the Union-Pearson Express which, at $27.50 a ride, most Torontonians cannot afford. Not to mention the rail will be diesel-powered.

And one obstacle to the Toronto-Hamilton relationship has been the sad state of connecting transit. Express GO buses exist. But the dearth of train linkage is pitiful. Weekday travellers from Toronto can take all-stops trains to Aldershot in Burlington during rush hour, and then bus to Hamilton. Four express trains run in the morning in the direction of Toronto only, and then send workers back to Hamilton on a few evening trains. On the weekends, it’s back to the bus. Most Hamiltime attendees were unaware of how to get to Hamilton and anticipated it being expensive.

As Hamiltime came to a close, people reassembled at our schoolbus at Bayfront Park. Several people dismounted bikes they borrowed from SoBi. Lissner remarked it was the best bike-share she ever used. Hamilton offers plenty of wisdom for TO: caution about neglecting old buildings; the beauty of interspersed nature and urbanism; the power of activated city councils with an agenda, and of citizens to act as change-makers, culture-brewers and watchdogs. The GT and H can co-miserate about amalgamation, reluctant or fearful city councils, urban-suburban divides, and other divides carved by natural edges like the Escarpment, Don Valley, or Davenport-St. Clair hill. Both cities have made harried decisions on long-term issues to suit a 17-day sports festival called Pan Am. A romantic rekindling is in the works for the GTHA. The challenge will be to support each unique entity in the union so it won’t be leachy for one.

For that, the Golden Horseshoe needs to support new imagination replete with new stories.

The post Lessons on rekindling a regional romance: a visit to Hamilton reveals a percolating urban revival Canada needs to watch appeared first on Spacing National.